Advertisers are often tempted to use sensationalist mass communication to promote their brand, which isn’t a good idea

It can seem like the news cycle these days is filled with sensationalism and attention-grabbing headlines, putting brands in a challenging and potentially compromising position.

Brands invest in advertising to attract attention, get the word out, and raise awareness about their product. In today’s saturated digital media environment, this can be a challenge because consumers have so many demands on their attention. Brands, understandably, want to meet consumers where they are—or rather, where their attention is—and find ways to break through the noise. However, this impulse can lead to the siren song of sensationalism.

Whether through advertising on sites that traffic in clickbait or by attempting to capitalize on the momentum of viral internet hoaxes, advertisers are often tempted to use sensationalist mass communication to promote their brand. This strategy is short-sighted.

Participation or affiliation with this type of advertising ultimately has a negative effect on a brand and its reputation. Brands can gain more ground by investing in accountable, ethical advertising that will drive results over the long-term.

Sensationalism

Sensationalist communication, which can sometimes be known as “Ragebait”- or content specifically designed to provoke strong emotions – is nothing new. In fact, it has a long history in American media through what used to be known as “yellow journalism.”

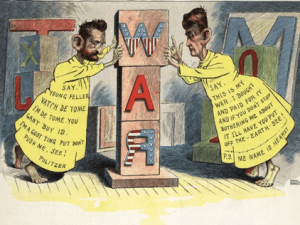

Yellow journalism emphasizes sensationalism over facts. It first emerged at the end of the 19th century when competition between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, and their respective newspapers, was fierce, with each paper duking it out for the public’s attention. The publishers realized that exaggerating stories to make them more dramatic meant they could sell more papers.

However, the consequences of this approach became clear with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. The newspapers had closely covered the Cuban struggle for independence and fanned the flames of the conflict, and while they didn’t cause the war, they played a central role in ginning up public interest and support.

Certainly, media and journalistic standards have evolved since then, but the internet is a breeding ground for sensationalist content. The internet enables anyone to be a publisher, promotes the rapid flow of information (with no gatekeepers), and floods people with so much content that headlines really have to be eye-catching to get clicks.

In the era of social media, more and more headlines use provocative messaging and promise stories that are “shocking” to attract attention. Other tactics include phrases like “one simple trick” or “what they’re not telling you.” The more people click on these headlines, the more people see the ads that are served there, and so the cycle continues.

Hoaxes

Today, this type of content can be divided into a couple of different categories. One category is hoaxes, like the Momo challenge or Tide Pods. As explained by Vox, an image of a “devilish bird-lady” named Momo somehow became a global panic about a dangerous “suicide game” that targeted children on social media. Parents were terrified that Momo would goad their children into violence while they used WhatsApp, watched YouTube videos, or played video games. But there was no evidence that the Momo challenge ever led to any violence—it was an “overblown internet hoax,” just like the idea that teenagers were ingesting Tide Pods or snorting condoms.

Satire, conspiracy, and “health” news

The internet can be an incredible resource to find information about current events, history, health, and more. It’s also a place where misinformation thrives, and it’s not always clear what is true and what is not. The internet makes it possible for people to find information that supports whatever they already believe, which fuels conspiracy theories. Anti-vaxxers, flat-earthers, and “birther” conspiracists are able to connect and share online and reinforce one another. This, in turn, leads people who don’t believe the conspiracy to try and correct the record. Each side infuriates the other. People may be mad, but they are engaged, which is what advertisers want.

Moreover, it can be tricky to discern online between what is satire and what isn’t. Sarcasm and nuance aren’t easy to pick up and people take things literally. Furthermore, many people aren’t educated on how to identify whether media sites, sets of facts, or scientific studies are truthful and valid. Content makers can take advantage of this ignorance to promote conspiracy theories and make money. One of the most notorious conspiracy mongers out there, Alex Jones of InfoWars, uses crazy ideas to shill products like nutritional supplements and survivalist gear.

Deep fakes

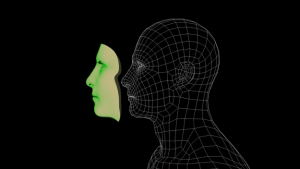

The lines between what is real and what is not are only going to blur further, thanks to technology that enables “deep fakes.” A deep fake is a “computer-generated replication of a person, saying or doing things they have never said or done,” as defined by The Guardian.

From celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence accepting an award to President Trump advising the Belgians on climate change, technology can make it impossible to decipher whether a thing actually happened or not. As deep fakes become more sophisticated, it will be even more important for consumers to rely on trusted platforms to parse what’s real and what’s not, and even more important for brands to focus their advertising in places not linked to falsehoods and deception.

The good (the bad, the ugly)

Certainly not all content that is designed for clicks is nefarious. Unorthodox food preparations and recipes tend to attract a lot of attention: Videos of people throwing pieces of Kraft cheese onto babies’ faces, or a bizarre-looking pot of “queso” have generated huge reactions. There are also positive challenges, like the ALS ice bucket challenge, which raised millions of dollars for disease research.

The internet has been around long enough at this point that sensationalist, viral content is not that hard to engineer. It’s a cheap laugh, and brands have to seriously question whether it’s valuable or ethical to engage with it.

While advertising alongside rage bait may garner eyeballs in the short term, it can also cause long-term reputational damage. There’s been a concerted effort from groups like Sleeping Giants to get brands to remove ads from platforms and shows that peddle in sensationalism and fear-mongering, like Breitbart and the Ingraham Angle.

Brands whose ads are associated with or run alongside deceptive or harmful content now get called out and held responsible, so companies have to weigh the value of reaching certain sets of customers with the need to preserve the dignity and positivity of their reputation. Either way, they may lose customers, so it has to be a question of ethics, integrity, and accountability.

Brands also have to make sure they know where all their ads are placed, which in a time of real-time bidding and programmatic advertising, is not always easy to keep a handle on. Brands should be very aware of where their digital advertisements get placed and where they are getting shared, perhaps through the use of a Digital Asset Management platform.

Staying on top of negative communication trends is key to a brand. By using a proprietary suite of social listening tools to analyze sentiment around the brands they represent, agencies can make their clients aware of these negative trends and how it may be impacting their customers. This can quickly affect messaging across all channels and placement that will quickly help brands navigate this negative ecosystem.

Final thoughts

In summary, effective advertising is about much more than how many people see an ad. It’s about building a brand’s reputation and developing a strategy that is sustainable in a constantly evolving landscape. There are new internet fads every day, and while they may attract attention in the moment, the next day will bring something new.

Trying to capitalize on this ephemeral, and often harmful, momentum is a losing strategy. Instead, brands should aim to optimize ROI by advertising in a way that is true to their vision and that doesn’t rely on the crutch of sensational or emotionally fueled communication to have an impact.

John Francis is Sr. Director of Digital Strategy at Hawthorne and responsible for creating digital advertising experiences for Hawthorne’s clients that emphasize conversions. He has a penchant for analyzing qualitative social and UX data in order to achieve the highest ROI for clients like BLACK+DECKER, Dexcom, Dyson, Gemmy, LeafFilter and Sengled among just a few. Understanding how people interact with information design is John’s passion. Prior to Hawthorne, John was the dean of the Keller Graduate School of Management/Information Sciences. For the 12 previous years he taught “Interactive Design, Usability, Marketing and Branding” at The Art Institute of California. Before his teaching adventures, he was the director of partner marketing with VERIO/NTT. Prior to his time with VERIO/NTT, John was Webmaster at America Online, where his team spearheaded the creation and launch of AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and strategically marketing the AIM software package, resulting in over 400M installations of the chat application.